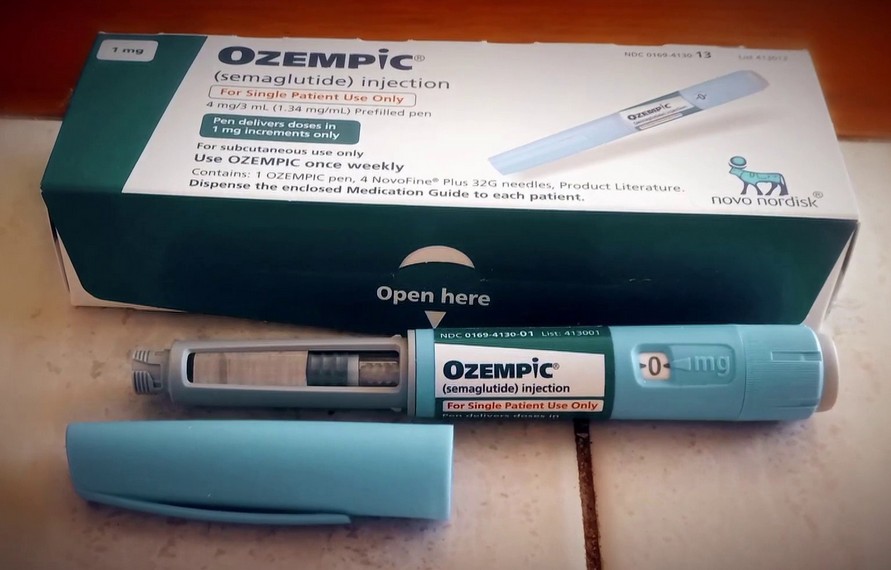

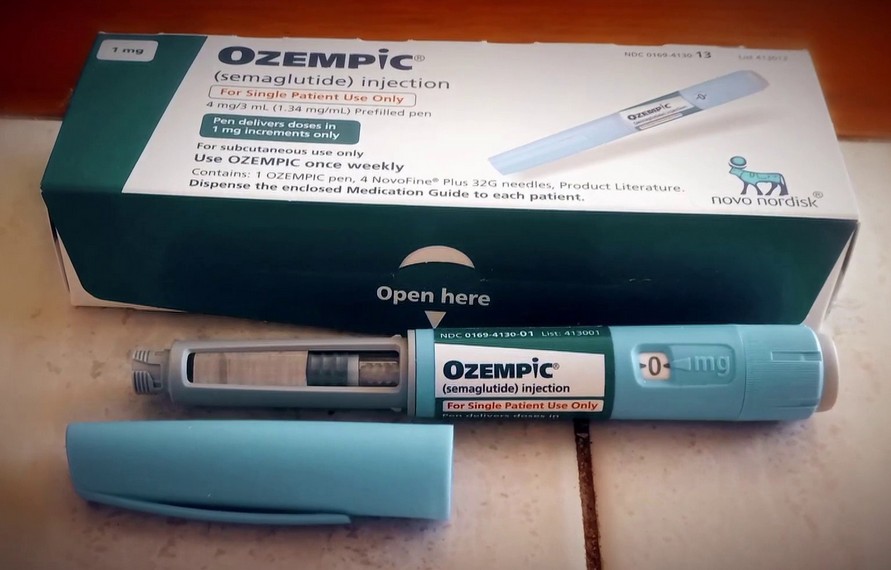

In the world of modern medicine, Ozempic has become something of a star. A once-weekly injection that lowers blood sugar, improves heart health, and — in a surprising twist that captured public imagination — causes significant weight loss. For many, it feels like a breakthrough. A lifeline. The answer they’ve been waiting for after years of failed diets, complications from diabetes, and declining health.

But behind the headlines and transformation stories, another narrative is quietly unfolding — not in doctors’ offices or pharmacies, but in policy rooms, budget forecasts, and Medicare’s swelling spreadsheets. A question is echoing, quietly urgent:

What if this miracle drug is too expensive to sustain?

Ozempic, and its cousins like Wegovy and Mounjaro, can cost over $1,000 per month. That number isn’t shocking in a pharmaceutical landscape where high price tags are the norm — but what is shocking is the scale. Because if even a fraction of the tens of millions of Medicare beneficiaries were prescribed these drugs long-term, the financial weight on the system would be unprecedented.

We’re not talking about a temporary surge in costs. These medications aren’t one-and-done treatments. They’re long-term, often indefinite. People who stop taking them tend to regain weight and lose progress. So once someone starts, the clock doesn’t stop — and neither do the bills.

Medicare, the government insurance program covering people over 65 and those with disabilities, is already strained. It’s a patchwork of rising demand, aging populations, and an increasingly expensive menu of medical options. And Ozempic isn’t treating a rare disease — it’s aimed at diabetes and obesity, two of the most widespread chronic conditions in the country. The potential demand is staggering.

One recent estimate suggests that if just 10% of Medicare enrollees were prescribed a GLP-1 drug like Ozempic, the annual cost could soar past $26 billion. That’s for a single drug class. For a single condition. And it’s only the beginning. As more drugs enter the market, with more people seeking access for diabetes, heart disease, and weight loss, the spending curve steepens.

And here lies the crisis no one wants to face head-on: Medicare wasn’t built for this. It was created in a different era, with different expectations, different life spans, and vastly different costs. Today’s reality — high-tech, high-priced, and high-demand — is rapidly outpacing what the system was ever designed to handle.

So what happens when a drug that can help millions also costs billions?

Do we limit access to only the sickest patients? Do we negotiate prices more aggressively, knowing pharmaceutical companies will push back? Do we expand Medicare’s drug cost reform powers — and how long will that take? Or do we simply let the system absorb the blow, and hope it holds?

For patients, this is more than a policy debate — it’s a deeply personal dilemma. Ozempic represents hope. It’s not just about weight or blood sugar. It’s about the ability to walk up stairs without pain. To avoid dialysis. To feel in control of a body that’s long felt like an enemy. It’s about staying alive — and living well.

But that hope comes with a price tag that Medicare may not be able to pay indefinitely.

The system is already walking a tightrope. Adding a tidal wave of $1,000-a-month prescriptions to the load doesn’t just shake the rope — it threatens to snap it.

This doesn’t mean we abandon the drug or deny care. But it does mean we can’t pretend this is business as usual. The rise of Ozempic has forced an uncomfortable but necessary reckoning: what happens when innovation outpaces infrastructure?

We’re going to have to make decisions — hard ones. About who gets access. About how much we’re willing to pay. About what “healthcare for all” really means when life-changing medicine comes with a price that could crack the system designed to provide it.

Ozempic is a miracle for many. But if we’re not careful — not bold, not honest — it could also be the tipping point that sends Medicare into a financial freefall.