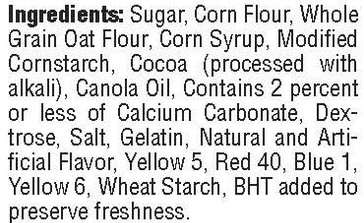

For decades, the food industry has operated like a magician — dazzling us with flavor, seducing us with convenience, distracting us with health-washed packaging, all while hiding the real ingredients behind the curtain. Salt, sugar, and fat were its holy trinity, engineered not for nourishment but for addiction. And for just as long, public health experts have sounded the alarm: these ingredients, in excess, are slowly hurting us.

But something’s changing.

Under growing pressure from governments, researchers, and fed-up consumers, the food industry is beginning to shift. Quietly, slowly, but unmistakably — it’s being pushed to reformulate. And one of the biggest drivers behind this is something called MAHA — Make America Healthy Again — a policy framework that’s part public health, part regulatory muscle, and part moral nudge.

MAHA is the kind of acronym that doesn’t make headlines — but behind closed doors, it’s rewriting recipes.

It doesn’t ban junk food. It doesn’t shout “bad” or slap shame-based warnings on packaging (though some countries do that too). What MAHA does is set targets: less sodium, less added sugar, fewer artificial additives. It nudges manufacturers toward better baselines — not by taking away choice, but by improving the default.

And it’s working — or at least starting to.

Cereals once loaded with enough sugar to double as dessert are being toned down. Soups and sauces are quietly having their sodium content reduced, fraction by fraction. Snack companies are retooling their ingredient lists — not dramatically, not overnight, but step by step, enough that your taste buds might not notice, but your body will.

The science behind it is simple: people adjust. If flavor profiles shift gradually, most of us adapt without resistance. If you cut the sugar in your morning cereal by 10% every year, you’re not going to riot — you’ll recalibrate. That’s the logic behind MAHA’s gentle push: meaningful change without panic.

Of course, not everyone’s thrilled. Reformulation is expensive. It means new research, new processes, new sourcing. And for an industry built on selling “more” — more flavor, more shelf life, more appeal — scaling back feels like moving upstream. There’s also the ever-present tension between health and profit: it’s easier to market a new product than to fix an old one.

But reformulation isn’t just about damage control anymore. It’s about survival in a world that’s waking up. More consumers are reading labels. More governments are passing policies. And more families are dealing with the consequences of an industry that sold us hyper-palatability and called it food.

So now, the same companies that once loaded up their recipes with bliss-point-level sugar are trying to reverse-engineer balance. They’re testing stevia, monk fruit, fiber blends, salt substitutes. It’s not perfect — and there’s plenty of marketing fluff hiding behind “natural” claims — but it’s a start. And in the food world, change often comes one reformulated product at a time.

What MAHA represents isn’t just policy. It’s a cultural shift. A rebalancing of priorities. A small but meaningful statement that food doesn’t have to make us sick to taste good — and that maybe the companies who helped create the problem can, if held accountable, help build the solution.

No, this won’t undo decades of damage. It won’t make Big Food a beacon of virtue overnight. But it’s something. A recalibration. A redrawing of the line between what we’ve accepted and what we deserve.

And for once, that change might just be baked into the product.